Slow Food Nations and the Eater Young Guns Summit: A New Chapter in Food

After attending both Slow Food Nations in Denver and Eater’s Young Guns Summit in Brooklyn, I’ve realized that food is our nation’s tool for revolution. The #MeToo movement shed light on the traumatic, violent, and misogynistic side of the restaurant industry. ICE raids exposed the racism and absence of humanity in our federal government, while the rise of sanctuary restaurants promoted the protection of an often underserved, unrecognized labor force. Finally, symptoms of hunger and the climate crisis have pushed us to reimagine urban environments as sites for agriculture to connect and empower chefs, diners, and neighborhoods to access local food sources.

Slow Food Nations and the Young Guns Summit were comprised of workshops, speaker series, and tasting tables in order to bring an awareness to food that goes beyond buzzwords like cage-free, sustainably harvested, and ethically sourced. Both events were able to challenge attendees to think about what a restaurant can be, and what we as diners, neighbors, and cooks, can bring to the table. These events showed me that—while our current cultural, environmental, and political systems are incredibly flawed—citizens are able to utilize the power of our democracy and stand together with their vote to create thriving neighborhoods, abundant economies, and sustainable ecosystems.

Slow Food Nations

Slow Food Nations is an annual festival that takes place in Denver, Colorado. It invites all people to attend and enjoy three days (July 19-21) of workshops, talks, and parties that are centered by one specific theme. This year’s theme was “Where Tradition Meets Innovation.” Some standout talks included: “Mental Health in Hospitality,” “African American Foodways,” and “Food on the 2020 Ballot.” While all events were greatly concerned with how consumers can use their buying power to reshape the modern food chain, there were two discussions I found particularly enlightening. The first was from a series of ticketed tastings dubbed “Meet Your Makers.” I attended one hosted by the Rocky Mountain Micro Ranch, a bug farm (yes, a bug farm) in Colorado.

“We eat loads of bugs without even realizing it,” said David Gordon, author of the 1998 cookbook Eat a Bug. “There are ‘acceptable levels’ of fruit flies in everyday products like ketchup. So if we see them, we won’t eat them?” The rhetorical question stunned the audience into an awkward silence. I looked down at my plate of orzo tossed with crickets, and three small soufflé cups filled with roasted mealworms, black ants, and chapulines (Mexican grasshoppers). There was a cold beet borscht with a dollop of sour cream, too. Wading in the pink broth were tiny bodies of—you guessed it—more mealworms.

“Bugs won’t save the world,” Micro Ranch founder and CEO Wendy Lu McGill said matter of factly, “but they are an untapped, nourishing, and sustainable food source.”

Top, Left to Right: roasted Ants, Chapulines, and Mealworms. Bottom, Center: Orzo with roasted Chapulines. Top Right, in Bowl: Cold Beet Borscht with roasted Mealworms. Bon Appetit!

We learned that per 100 grams of crickets, there are 13 grams of protein, 9 milligrams of iron, and 76 milligrams of calcium. For reference: 100 grams of chicken contains 19 grams of protein, .9 milligrams of iron, and 14 milligrams of calcium. (Suddenly that plate of cricket orzo looked much more appealing.) Wendy’s plethora of graphs and charts revealed that it takes more than 5,800 gallons of water and 10,000 grams of feed to produce just over two pounds of beef (your average cow is between 1,000-1,800lbs). But for two pounds of those chapulines? Just 1,700 grams of feed and barely one gallon of water. Finally, livestock production utilizes 70% of arable farmland, either directly or indirectly (for feed). With vertical farming techniques and the miniscule size of these yummy, creepy-crawlies, insect rearing for consumption takes up much less land, generates less waste, and uses much less energy.

Now in Chipotle, Adobo, or Plain! Buy Here

To me, it seems our bug aversion is grounded in our historical and cultural conceptions of “food.” While insects are eaten in Mexico and South America, 36 countries in Africa, and 29 countries in Asia, insect farming in North America was never part of the “American Dream.” Instead, we wanted acres of crops, barns of livestock, and “amber waves of grain.” Compared to the rest of the world, our food preferences developed around a much narrower concept of the food chain. As a result, we created a systems of agriculture that rendered us dependent on unsustainable chains of production. Add an ever-increasing, hungry population to the equation, and you get fast food, processed foods, commodity crops, and a gigantic carbon footprint.

After my bug-filled lunch, I headed over to a talk called “What the Fish?” with Paul Riley (beast+bottle, Coperta, Pizzeria Coperta), Gunnar Gislason (Agern), Patrick Dunaway (Niceland Seafood), Derek Figueroa (Seattle Fish Company), and moderator Sheila Bowman (Seafood Watch). Like Wendy and David, these industry folks also addressed this pivotal moment for producers, diners and restauranteurs to change the future of food.

“I hate the phrase ‘sustainable seafood,’” declared Figueroa. “It’s really about responsible seafood and responsible harvesting. What you catch isn’t put back. Of course that makes it unsustainable.”

To combat the problem of overfishing, aquaponics and aquaculture seem to propose a viable, modern solution. Edenworks in Brooklyn, for example, has constructed a closed-loop ecosystem that annually produces 50,000 pounds of tilapia and 130,000 pounds of leafy greens…all with 95% less water inside a 10,000 square foot facility. There is also Aerofarms in New Jersey and another company, FarmedHere, which has set out to build a nationwide network of vertical farms (the first is a 60,000 square foot facility in Louisville, Kentucky).

While aquaponics is environmentally sustainable system, Riley delved deeper into the cultural complexities of the issue. He went on to remind us that consumers have been taught to enjoy only certain types of seafood—filets of salmon, cans of tuna, and bags of shrimp—which not only mean poor conditions on fish farms trying to keep up with supply and demand but also incredibly high amounts of food waste: fish collars, heads, bones and tails are thrown away in the commercial market without a second thought. Restaurants and chefs, then, attempt to offset food costs and waste by providing more variant, fish-forward menu items (Grilled tuna collar, anyone?). Consumers, though, are still afraid to try a fish part they haven’t seen before.

“It’s important to know where your fish is coming from,” Riley concluded, alluding that this should give diners the confidence to try more unique seafood. “Don’t be afraid to do your research and ask your server, grocer, and chef questions.”

Dunaway, the fish lover and purveyor, finally chimed in: “Buy whole fish, please. Mongers want to teach you new ways to use new seafood.” Indeed, the panel said no amateur cook should fear searing scallops or steaming mussels at home. “The fishermen are embracing innovation,” he continued, “and now the consumers have to follow suit.”

Below, left to right: Oysters and Arctic Char from the festival’s “Zero Waste Dinner”

The panel closed with a final message from Dunaway in regards to changing this conflicted kettle of fish. “If we keep bringing our fish closer to our consumers and restaurants, then the product is fresher, the supply chain is healthier, and the waste is lesser.” He revealed to us that plastic and Styrofoam from packaging and transporting fish is a huge problem for our environment: when these products are thrown away, they end up in the oceans and are eaten by the fish. When we eat those fish, we’re also eating that plastic we thought we disposed of. At the end of the day, the fish we eat are much more connected to us than we think.

Our food choices have a direct impact on the planet. While it seems daunting to try to take down our nation’s meat and fish industries, there are plenty of local opportunities to cultivate change and harbor more fruitful connections to our food supply. It’s important for consumers and diners to be more curious about their role in the food system and create new opportunities by asking questions, and holding their purveyors and distributors more responsible for their product. At the local level, an expression of interest or a growing network of support can go a long way.

The Eater Young Guns Summit

The Eater Young Guns Summit is a celebration of 12 unique and talented, food-centric individuals under the age of 30 that have less than five years’ experience in the restaurant industry. Members of the 2019 class included Jason Chow (Butcher & Larder), Jacob Harth (Erizo), Claudia Martinez (Tiny Lou’s), and Ashleigh Shanti (Benne on Eagle). These young guns not only display a great love for food and drink, but they also embody and emanate a very special future of food. Keynote speaker Marcus Samuelsson therefore presented the question of a restaurant’s role in a society obsessed with food. While consumers should continue to worry about waste, access, and a product’s integrity, the population needs to conjure a more inclusive image of American foodways. In other words, our society must not only think about sustainable systems of agriculture, but also sustainable economies for those who own restaurants, serve food, and transport product.

The summit’s first panel discussion, “Goodbye Food World, Hello City Hall,” further examined Samuelsson’s ideas. Moderator Meghan McCarron questioned both Julia Turshen (cookbook author, EATT founder) and Shakira Simley (Nourish and Resist, Bi-Rite) about how food contributes to our national conversation, particularly through the lens of restaurants and hospitality.

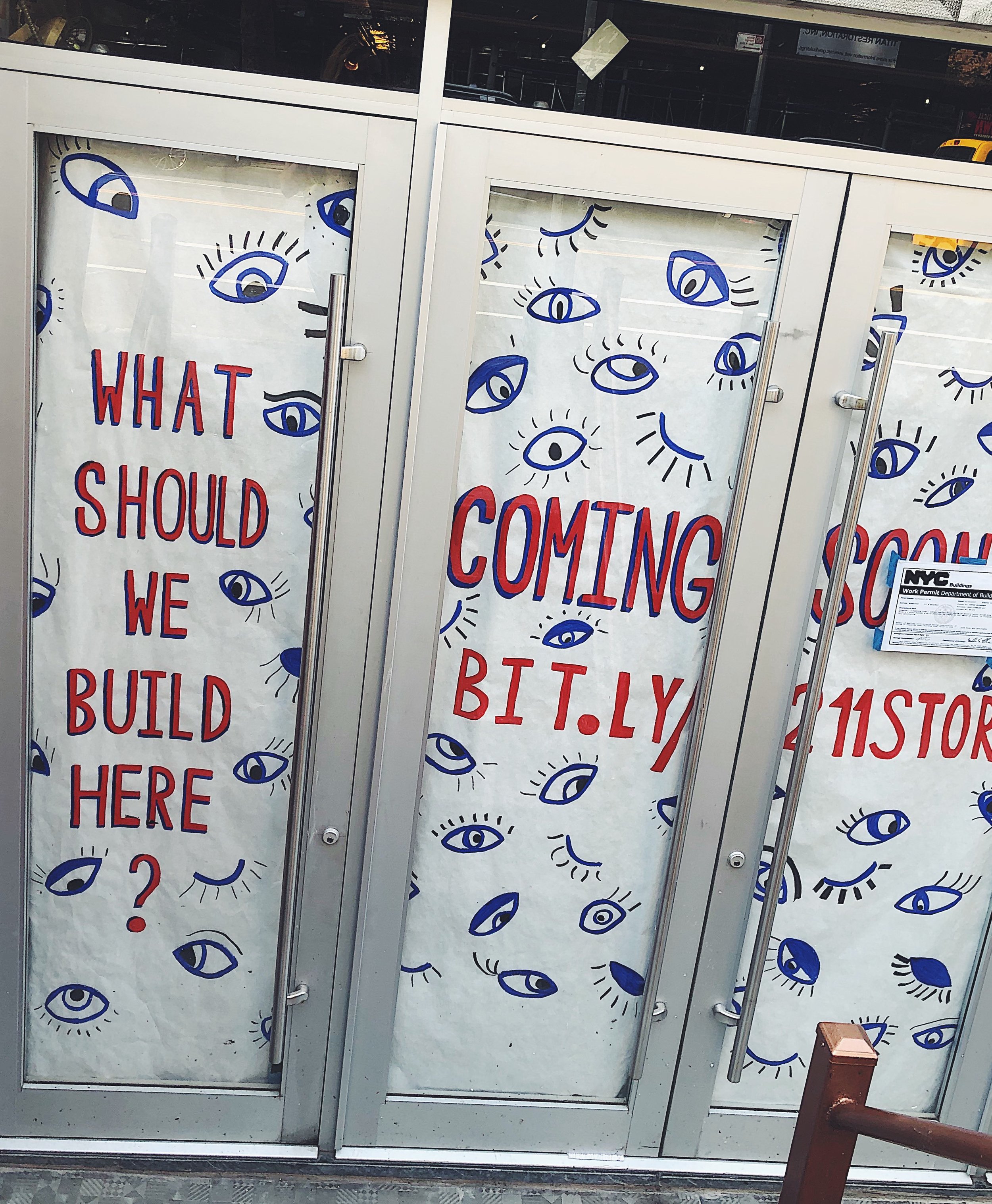

Seen in Chinatown, NYC

“There’s a certain amount of social responsibility a restaurant must have,” Simley began, “but that responsibility must first be as locally grounded as possible.” She and Turshen went on to explain that while food is the ultimate tool for organization, the restaurant is the vessel in which that organization takes place. However, as rents rise and penalties for vacancies threaten landlords, larger hospitality companies and restaurant groups soon make their way on to the scene, completely changing the social and economic landscape of the neighborhood.

Simley made the point: “Communities have all the power to determine which businesses open and close. There are surveys to take, representatives to contact, and zoning laws to enforce. We can all take advantage of these resources to create the neighborhoods we want.”

She informed the audience of certain legal actions like a legacy certification, which keeps businesses tied to family members, and another called a “community benefits agreement,” where a developer is contractually obligated to provide specific amenities or mitigations to its surrounding neighborhood.

“Instead of building an apartment building on an empty plot, contact your district representative and request a community garden,” Turshen added, “and have one of your restaurants host a neighborhood dinner to talk about local issues.”

Simley and Turshen agreed that restaurants are a tool for change, but it is up to citizens to gather in those restaurants to exchange the ideas that will spark change. Restaurants are not only a place to enjoy an afternoon or evening of good food, but they are also staples for communities that strengthen relationships and allow minds and bodies to flourish.

It’s clear that creating sustainable businesses is just as important as creating sustainable food sources. Devita Davison (FoodLab Detroit) and Martha Hoover (Patachou Inc.) think these two concepts are one in the same. Restaurants and chefs have spent a great deal of time worried about whether their food is sourced ethically—they believe that their duty to their diners is to provide a near-perfect meal with near-perfect ingredients. But when the only concern is food, how does a restaurant suffer?

“Americans have no idea how much food costs,” Devita asserted. Indeed, food and beverage costs are between 25-30% of a total spending budget; if the owner pays $1.00 for a food item, it will be about $3.40 on a menu. Seems like quite a markup, right? This is because the listed price has to help pay for other aspects of the restaurant like taxes, licenses, rent, food transportation, and wages. So when you pay $14.00 for your avocado toast (and $3 extra for a poached egg), you are also paying employees, covering food costs, and helping with the rent (read more here). In an ideal world, the system should work…but fast food and and Big Ag has led us to believe that we should be able to access whatever food we want, at any time, and at a the cheapest price. Some restaurants have tried to be more transparent to helps diners understand. At Giant in Chicago, for example, each receipt states that 3% of the total bill helps to pay for employee health care. No tipping policies have also helped to alleviate wage disparities between front and back of house. But at the heart of this, both Davidson and Hoover agree that it is the diner’s misunderstanding of their role in the restaurant business.

While many go out to eat for the purpose of a finely curated and delicious evening, it’s important to understand the implications of this obstinate power dynamic between diner and servers. Thus “restaurants have to implement their own unique social and economic systems,” said Hoover, “at Patachou, we value our employees; we provide assistance plans and an emergency relief fund. Equitable food systems don’t just mean sustainable ingredients…they also require sustainable livelihoods.”

Patachou, Inc. operates more than ten restaurant concepts in the Indianapolis area and are maintained through the company’s five grounding principles: food sourcing, customer experience, leadership opportunities, sustainability, and commitment to the community. Not only do Hoover’s establishments support more family farms in Indiana than any other restaurant in Indianapolis, but The Patachou Foundation—a 501c3—serves healthy meals to at-risk and food insecure children. Patachou’s vision is therefore not just rooted hospitality, but it is also dedicated to sustaining the livelihoods of those directly and indirectly involved in the food system.

Devita and Martha therefore reminded us all of the 3Ps in every business: people, product, and planet. This triple bottom line approach, Devita believes, will set forth the creation of more “food sovereign” cities, which are less dependent on mass market systems of agriculture and are deeply dedicated to supporting local food entrepreneurship. She used her own FoodLab as evidence—the organization gathers specialty makers, processors, retailers, and distributors in the Metro Detroit area to create stronger networks of communication and provide resources to keep local businesses thriving.

“Restaurants are spaces of conviviality,” she concluded, “they are places where life’s most precious moments occur…It is then our job as community members to support and help provide for those who make these places possible.”

Conclusions

Slow Food Nations taught me to reconsider the components of the food chain in order to create a more diverse and sustainable way of eating. This festival also challenged me to seriously consider my everyday food choices in order to help protect the environment and promote responsible farming practices. The Eater Young Guns Summit pushed me to rethink the concept of the restaurant beyond that of a transactional food and hospitality experience. Summit speakers exposed the power of a democracy at the local level to create fairer economic systems, healthier food supplies, and more vibrant neighborhoods. It is clear that the role of food is vital in managing and shaping our social, cultural, and political aspects of living. Our dependency on massive and over-industrialized systems of agriculture has rendered our nation dependent on unsustainable, unhealthy, and unfair foodways. These events have made clear to me that our federal government can neither directly nor immediately alleviate symptoms of food insecurity, poverty, and climate change. However, our political system has given us the ability to establish organizations, networks, and resources committed to helping their neighbors and greater communities. Now more than ever, we must “vote with our forks” and create a new culture of food that is grounded in locality, sustainability, and commitment.

Resources:

Find Your Congressional Representative

Join Slow Food USA or find your Local Chapter

Seafood Watch

Join or find resources at the Small Business Administration

Learn about Census 2020