The Weaponization of Food (2/2), Your Tool For Change

If you have not read part one yet, click here.

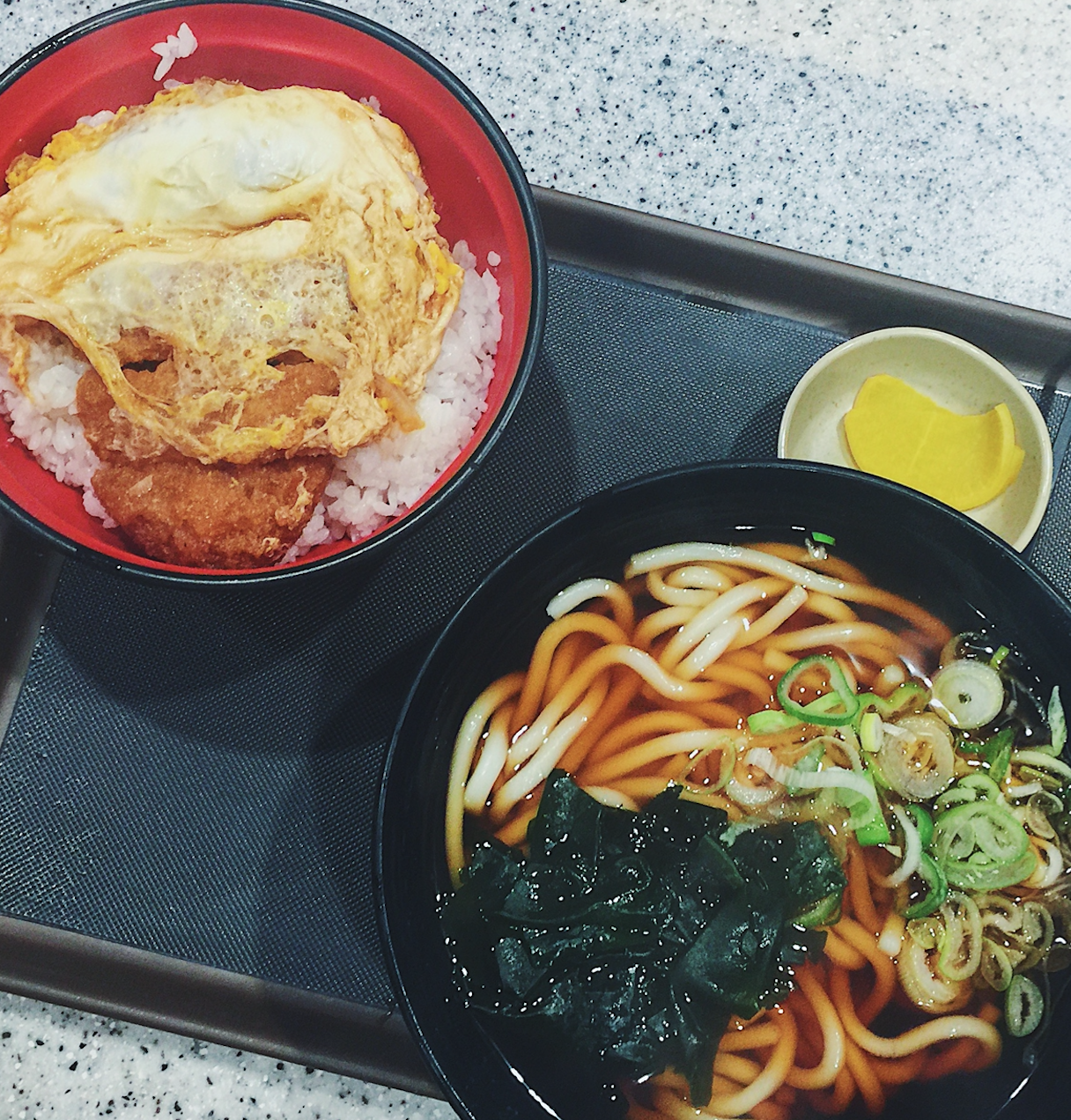

Our first stop was Tokyo: I had sushi in Tsukiji Market, ate yakitori washed down with beer at izakaya stalls, and slurped down infinite bowls of udon and ramen.

In Kyoto, we lived lavishly and indulged in gorgeous kaiseki meals, including a trip to the legendary Hyotei. After late nights at the bars, we gorged on fluffy egg sandos from Family Mart and sat by the water glistening from the light of the street lamps. Our visit to Nishiki market was also a highlight; I ate doriyaki, uni out of the shell, a tiny squid on a skewer with a soft boiled quail egg inside its head, and endless amounts of pickled vegetables. We had okonomiyaki in Hiroshima, and then ventured to Miyajima island. I remember sitting on a wall parallel to the shoreline—smelling the salt of the sea and feeling the pleasant warmth of the sun—enjoying gargantuan grilled oysters, eel rice, and steamed buns. And finally Osaka; I couldn’t even begin to tell you how many takoyaki I popped into my mouth.

I let for Japan 108lbs, and came back 3 weeks later at 119.

I won’t lie to you, reader, the trip was hard. After some nights I’d wake up in sobs, hating myself for consuming so much food. I’d have days where I would not want to leave the hotel room, ashamed of body and seeking to hide away. I’d look in mirrors with horror upon seeing the tiniest decline in muscle tone, my cheeks fuller and flushed with life. I’d have sleepless nights in which my mind would endlessly torture me with imagined conversations with friends, their exclamations of “you put on so much weight!” ringing in my ears. Ultimately my mind kept telling me that body I had “worked so hard for” was being sacrificed for purely hedonist desires.

But I am so grateful I had my sister by my side, holding my hand in times of trouble, laying by my side to soothe me back to sleep; being so impossibly patient as my battle waged on. With her love and kindness, I was finally seen, heard, and loved.

And so when that scale read 119lbs, something inside me changed. Every pound gained was a memory made, something to be cherished. This new physical form was not something I was ashamed of; it was the embodiment of a mended relationship. I threw myself into the deep end and pushed myself to my psychological limits. I looked straight down the barrel of the gun and overcame the monster in my mind. It was the proudest moment of my life. Food was no longer a weapon that brought me pain and sadness. It no longer controlled me. Food became my joy again—and my body became a vessel in which feelings of love, curiosity, fun and fulfillment were (and still are!) held forever.

Today I am still in recovery. My weight fluctuates between 133-143lbs. I use “recovery” and not “recovered” because I, like many others, still have their good days and bad. Some mornings I wake up not even able to look at myself. Other days I’ll put on my sexiest dress and go out with my girlfriends on a Saturday night. I am still learning to live with depression, a diagnosis received shortly after my ED’s, which is another monster all its own. The human mind is a fickle thing, and dealing with trauma is an ongoing and undulating process. But no one should ever have to go it alone. While the internet today may provide certain opportunities to create communities of support for those who are suffering, the opposite is also true. Social media has presented us with too many images of bodies we perceive as “ideal”, and it initiates a never-ending competition between whose body is “the best”. But remember, reader, what it is you are looking at: an image. It is not a living, breathing, moving body. It is static and exists in a world that is purely based on appearance and presentation; it is just a snapshot of one’s existence, often staged to be pleasing only to the eye.

Reader, you are so much more than an image. We are all so much more than an image. Trying to achieve a body like someone else’s is to throw away your individuality, to eliminate all the incredible things that make you who you are. My downfall was that I was letting these images of others’ bodies control what I thought my own should look like. I gave myself up to an industry based purely in marketing tactics, aesthetic and style rather than trust my own knowledge of health, nutrition and science. So when you see a fitness model or body builder, a wellness coach, or even your favorite instructor sharing the things they eat, don’t think you have to eat that too. These people are not always nutritionists, dieticians, or medical doctors. They know what is best for their bodies, not yours. Thus I perceive that in the fitness industry, posting pictures of “healthy foods” (in particular) has become a subtle yet effective expression of authority and control. As a fitness entrepreneur’s online and public presence increase, audiences begin to rely on them for advice and inspiration (see: the Instagram “influencer”). And while it’s perfectly okay for an audience to inquire or seek food recommendations by those they want to look like, the implications are complex. On one hand, it holds the influencer accountable for their actions, as the things they ingest simultaneously become both a personal choice and also a public expression of how it relates to their overall image. Food thus no longer becomes a nutritional medium, but the subject for content creation and a direct assertion of one’s aesthetic or “brand”. In other words, the viewer perceives: “if you eat like me, then maybe you can look like me, too!”.

And this is the weaponization of food. When an individual sees an image of another’s food, the onlooker involuntarily reflects upon their own food choices. Often, this triggers immediate feelings of dissatisfaction. Maybe you’re also eating some hardboiled eggs on a bed of organic mixed greens with your dressing on the side. So you are frustrated that you still don’t have a body similar to that Soul Cycle instructor’s. Or maybe you see your favorite lifestyle blogger posting a picture of an awesome “vegan breakfast” while you’re about to enjoy a bacon egg and cheese from your corner bodega. In both scenarios, the viewer’s choice is subconsciously deemed inferior, a contribution to their “less than ideal” body. And so with a simple image, the “influencer” has done their job: food has become a weapon of power, inducing its audience to engage in critical self-reflection and obey a set of unspoken yet deeply embedded set of rules not of their own design. It is nothing more than a reiteration of the “fat” and “skinny” dialogue, letting others design our ways of being; that one person’s choice is “right” and the others are “wrong”. This is the downfall of modern society and the age of technology. With access to so many opinions and images, we have lost our ability to both take pride in and also trust ourselves in choosing the ways we want to live.

When food and fitness intersect, there is no balance of power. Fitness is an industry; health is a science. Health is an understanding of an individual’s needs; fitness is a strictly defined method of living, a rigorous and image-driven way of belonging. Humans will always hunt for the best “fitness” solution (the most effective juice cleanse, the tastiest “keto-friendly” beef jerky, and the optimal “low carb” fruits and vegetables) and look to those who embody that solution. I myself am a fitness instructor, and I too am often asked to post about the foods I consume on a daily basis. But I want us all to become more aware of the hidden implications behind this kind of expression. With food—cooking, eating, sharing and enjoying are all characteristic of the human experience. But there are also trials of loneliness, deprivation, sadness and oppression. There is no definite method of engagement when it comes to eating; that’s what makes it so fun! Thus we need not judge each other or seek another’s validation when it comes to our food choices. It is your own life to live; your own steps to take at your own pace. Ultimately it’s important to treat bodies—your own or another’s—with love, nourishment, and kindness. But when food is weaponized, we become hyperaware of our consumption and blame ourselves for this culturally-induced dissatisfaction. Therefore, we have to acknowledge food as this tool so that some balance is restored. I believe that when food in the fitness industry is wielded more responsibly—no longer a marketing tactic, but a free and open discussion—bodily difference is appreciated and shame dissolves. No longer do we have to adhere to an “ideal” and potentially harm ourselves in the process. No longer do problematic relationships with food have to hide. I do not want to exist in a world of images and falsities. I want to live with other breathing, moving, living bodies. Thus if we come to understand that there is so much more to humanity than our physical form, we can accept the kindness, pride, compassion, beauty and love both food and our people have to offer.